Uterine Sarcoma Treatment

Introduction

Invasive neoplasms of the female pelvic organs account for almost 15% of all cancers in women. The most common of these malignancies is uterine cancer, specifically, endometrial cancer. Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. An estimated 40,100 cases are diagnosed annually, leading to 7470 deaths. It is the fourth most common cancer, accounting for 6% of female cancers, following breast, lung, and colorectal cancer. However, it has a favorable prognosis because the majority of patients present at an early stage, resulting in only 3% of cancer deaths in women.

History of the Procedure

Cancer of the uterine corpus is the most common pelvic gynecologic malignancy in the United States and in most developed countries with access to sufficient health care. Approximately 95% of these malignancies are carcinomas of the endometrium. The most common symptom in 90% of women is postmenopausal (PMP) bleeding. Most women recognize the need for prompt evaluation, although only 10-20% of women with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding have a gynecologic malignancy. Because of this prompt evaluation, 70-75% of women are diagnosed with surgical stage I disease.

Currently, no screening tests for cancer of the uterus are recommended for asymptomatic women. No evidence suggests that routine endometrial sampling or transvaginal sonography to evaluate the endometrial stripe in asymptomatic women has a role in early detection of uterine cancer, even in women who take tamoxifen after breast cancer. The early detection, presenting symptoms, and higher survival rate make it unlikely that screening will have a successful impact on earlier detection and increased survival rate.

Sixty percent of endometrial carcinomas are adenocarcinomas. Other histologic subtypes include adenosquamous, clear cell, and papillary serous carcinomas. Sarcomas make up about 4% of uterine corpus malignancies, including carcinosarcomas or mixed homologous müllerian tumors, 48-50%; leiomyosarcomas (LMSs), 38-40%; and endometrial stromal sarcomas (EESs), 8-10%. The remaining sarcomas are made up of heterologous tumors—tumors that contain histologic components foreign to the uterus, such as rhabdomyosarcomas, osteosarcomas, and chondrosarcomas. This article discusses endometrial cancer and uterine sarcomas.

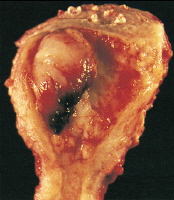

Adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. This tumor, which occupies a small uterine cavity, grows primarily as a firm polypoid mass.

Problem

Uterine cancer is defined as any invasive neoplasm of the uterine corpus.

Frequency

Approximately 40,100 women were predicted to develop this form of malignancy in 2008 in the United States. After doubling in the early 1970s, the incidence of uterine cancer has remained fairly constant. In 2008, 7,470 deaths were predicted. While endometrial cancer affects reproductive age as well as postmenopausal women, 75% of endometrial cancers occur in postmenopausal women, with the mean age of diagnosis at 61 years. Premenopausal women are at increased risk if they have certain risk factors.2 The most common low-grade endometrioid endometrial cancers have been associated with obesity, nulliparity, anovulatory menstrual cycles, diabetes, and hypertension. In addition, these younger women are at higher risk for a synchronous primary ovarian cancer, with a rate up to 19-25%.

Another group of women at increased risk of premenopausal endometrial cancer are those with Lynch II syndrome, also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). This is an autosomally dominant germline mutation in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MSH1, MSH2, MSH6) and accounts for 9% of patients younger than 50 years with endometrial cancer. These mutations lead to microsatellite instability in 90% of colon cancers and 75% of endometrial cancers. Besides colon cancer, women affected have a 40-60% risk of endometrial cancer by age 70 years, compared to a baseline population risk of 1.5% at the same age. Fifty-one percent of women had endometrial or ovarian cancer diagnosed first as the sentinel cancer. These women are also at increased risk for cancer of the ovary, stomach, small bowel, hepatobiliary system, pancreas, brain, breast, and ureter or kidney.

Incidence of endometrial cancer is higher among Caucasians compared with Asian or black women; however, mortality is higher among blacks. This is thought to be due to poor access to care and presentation at more advanced stages. Uterine sarcomas, regardless of the histologic subtype, are more common in black women. Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) tends to occur more often in women aged 30-50 years compared with carcinosarcomas and endometrial stromal sarcomas (EES), which have a much higher incidence in women older than 50 years.

Etiology

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma can be due to excess estrogen from various sources, either exogenous or endogenous. Exogenous sources have included unopposed estrogen replacement therapy or tamoxifen use. Tamoxifen increases endometrial cancer risk by its agonist activity on the estrogen receptors on the endometrial lining. Endogenous estrogen sources include obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) with anovulatory cycles, or estrogen-secreting tumors such as granulose cell tumors. Increasing body mass index has been associated with increasing risk of endometrial cancer.Research has found a relative risk of 3 in women 21-50 lb overweight and relative risk over 10 in women more than 50 lb overweight. Androstenedione is converted to estrone, and androgens are aromatized to estradiol in the adipose tissue, leading to higher levels of unopposed estrogen in obese women. See Table 1.

Table 1. Factors Contributing to Endometrial Cancer

| Risk Factor | Number of Folds Increased Risk |

|---|---|

| Estrogen only hormone replacement therapy (HRT) | 2-10 |

Obesity |

2-20 |

PCOS, chronic anovulation |

3 |

Tamoxifen |

2-3 |

Nulliparity |

2-3 |

Early menarche, late menopause |

2-3 |

Hypertension, diabetes |

2-3 |

| Risk Factor | Number of Folds Increased Risk |

| Estrogen only hormone replacement therapy (HRT) | 2-10 |

Obesity |

2-20 |

PCOS, chronic anovulation |

3 |

Tamoxifen |

2-3 |

Nulliparity |

2-3 |

Early menarche, late menopause |

2-3 |

Hypertension, diabetes |

2-3 |

The other factors associated with increasing one’s risk of endometrial cancer are believed to be related to the same mechanism of increased levels of unopposed estrogen. Nulliparity and infertility are likely related to chronic anovulation. Increased alcohol use can elevate estrogen levels. Late menopause and early menarche can be associated with more anovulatory cycles and thus more unopposed estrogen.

While there is no evidence that screening for endometrial cancer in high-risk populations, such as patients on tamoxifen or patients who have HNPCC syndrome, decreases mortality, some societies advocate screening with endometrial biopsies starting at age 35 years in patients with HNPCC.

Factors that decrease unopposed estrogen are associated with decreased risk of endometrial cancers. The use of combination oral contraceptive pills for 12 months decreases the risk of endometrial cancer by more than 40%.Similarly, postmenopausal women taking the combined estrogen and progesterone hormone replacement therapy have also been found to decrease their rate of endometrial cancer.Smoking is thought to decrease the risk of endometrial cancer by decreasing estrogen levels as well as leading to earlier menopause.

The following have been identified as risk factors for the various uterine sarcomas. Risk factors for uterine LMS may include early menarche, late menopause, and African American race. Women with a history of pelvic radiation are at greatest risk for carcinosarcomas and, to a lesser extent, LMS. Nulliparous women may be at greater risk for both types of sarcomas.

Pathophysiology

Endometrial cancers are divided into 2 classes, each with differing pathophysiology and prognosis. More than 80% of endometrial carcinomas are type I and are due to unopposed estrogen stimulation, resulting in a low-grade histology. It is often found in association with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, which is thought to be a precursor lesion. Type II endometrial cancers are thought to be estrogen independent, occurring in older women, with high-grade histologies such as uterine papillary serous or clear cell.

Endometrial cancer may originate in a small area (eg, within an endometrial polyp) or in a diffuse multifocal pattern. Early tumor growth is characterized by an exophytic and spreading pattern. As noted in Clinical, this growth is characterized by friability and spontaneous bleeding, even at early stages. Later tumor growth is characterized by myometrial invasion and growth toward the cervix. Four routes of spread occur beyond the uterus:

- Direct/local spread accounts for most local extension beyond the uterus.

- Lymphatic spread accounts for spread to pelvic, para-aortic, and, rarely, inguinal lymph nodes.

- Hematologic spread is responsible for metastases to the lungs, liver, bone, and brain (rare).

- Peritoneal/transtubal spread results in intraperitoneal implants, particularly with uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC), similar to the pattern observed in ovarian cancer.

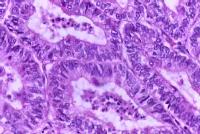

Adenocarcinoma of the endometrium, the most common histology, is usually preceded by adenomatous hyperplasia with atypia. If left untreated, simple and complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia progress to adenocarcinoma in 8% and 29% of cases, respectively. Without atypia, simple and complex hyperplasia progress to cancer in only 1% and 3% of cases, respectively.Typical histologic pattern, specifically cribrifo...

Typical histologic pattern, specifically cribriform glandular appearance, of endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Increased nuclear atypia and mitotic figures are present. Endometrial adenocarcinoma is histologically characterized by cribriform glands (or glandular crowding) with little, if any, stromal tissue between the glands. Nuclear atypia, variation in gland size, and increased mitoses are common in adenocarcinoma. Well-differentiated tumors may be confused with complex hyperplasia with atypia histologically. Likewise, poorly differentiated tumors might be confused with sarcomas histologically. All papillary serous and clear cell histologies are considered grade 3. The differentiation of endometrial cancers is one of the most important prognostic factors. Grade 1, 2, and 3 tumors make up approximately 45%, 35%, and 20%, respectively, of adenocarcinomas of the endometrium. The 5-year survival rate of clinical stage I cancers is 94%, 88%, and 79% for grade 1, 2, and 3 tumors, respectively. The degree of histologic differentiation of adenocarcinoma of the endometrium as defined by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) is as follows:

- FIGO grade 1 - 5% or less of solid/nonglandular areas

- FIGO grade 2 - 6-50% of solid/nonglandular areas

- FIGO grade 3 - More than 50% of solid/nonglandular areas

Less histologic differentiation is associated with a higher incidence of deep (ie, greater than one half) myometrial invasion and lymph node metastases. Subsequently, the depth of myometrial invasion and presence of tumor in the lymph nodes is directly related to recurrence rates and 5-year survival rates.

Histological variants

The most common histologic subtype of endometrial cancer is endometrioid adenocarcinoma, accounting for about 75-80% of endometrial cancers. Less common histologies include adenosquamous (2%) and mucinous (2%). When corrected for grade, however, the presence of squamous components has not been demonstrated to cause a significant difference in prognosis compared to pure adenocarcinomas. PTEN mutation is thought to be an early event in low-grade endometrial cancers and is found in 55% of hyperplasia and 85% of cancers, whereas it is not found in benign endometrium.

Approximately 15-20% of endometrial cancers are type II cancers with papillary serous or clear cell histologies. Papillary serous histology represents 5-10% and clear cell histology represents less than 5% of endometrial cancers. They are considered high grade with poor prognosis. They have a propensity for early nodal or upper abdominal spread even with minimal or no myometrial invasion. The p53 mutation is more common in high-grade tumors, and ERBB-2 (HER-2/neu) mutation is common in type II cancers. Even with surgical stage I cancer, the 5-year survival rate is 60%. Histologically, uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) resembles papillary serous carcinoma of the ovary. Although adjuvant chemotherapy is helpful, UPSC does not have the same duration of response to cytotoxic agents (eg, paclitaxel, carboplatin) as its ovarian counterpart.

In regards to uterine sarcomas, specifically LMS, the histopathologic diagnosis can be unclear until the time of definitive surgery. Diagnosis of LMS is dependent on the number of mitoses (or mitotic count) and the degree of cellular atypia. The diagnosis of LMS versus leiomyoma and leiomyoma with high mitotic activity or uncertain malignant potential is based on the metastatic potential of the tumor. The mitotic count and cellular atypia correlates to this metastatic potential.

Although controversy continues to exist regarding the diagnosis of LMS, several studies support the theory that if the mitotic count is less than 5 per 10 high-powered fields (HPF), the tumor is a leiomyoma with negligible metastatic potential regardless of the presence of any cellular atypia. Likewise, the tumor has a high metastatic potential and is considered an LMS, regardless of the degree of cellular atypia, if the mitotic count is greater than 10 per 10 HPF. Some believe that mitotic count alone is not a good indicator of metastatic potential.

Carcinosarcomas or homologous mixed müllerian tumors (MMT) typically have an endometrioid carcinoma, usually a higher grade, and an undifferentiated spindle cell sarcoma. The sarcomatous portion of the tumor may exhibit an endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) pattern, if differentiated. MMTs are termed heterologous only if identifiable extrauterine histology is demonstrated. MMTs are characterized by early extrauterine spread and lymph node metastases. Extrauterine disease and lymph node metastases are directly related to depth of myometrial invasion and the presence of cervical disease. The presence of heterologous elements does not seem to affect prognosis in terms of the initial extent of disease. New evidence points to a substantial expression of c-kit receptors in MMTs.

ESS can be divided into 2 categories: low-grade ESS (LGESS) and high-grade ESS (HGESS). LGESS is characterized by fewer than 5-10 mitoses per 10 HPF and minimal cellular atypia. These tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 50% but demonstrate indolent growth and late recurrences. HGESS have a greater mitotic count and degree of cellular atypia. Risk of recurrence in both LGESS and HGESS is determined not only by histological characteristics but also by surgical stage and extent of disease.

Presentation

More than 90% of patients with endometrial cancer will present with abnormal vaginal bleeding, whether it is menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, or any amount of postmenopausal bleeding. Approximately 10% of postmenopausal bleeding will lead to a diagnosis of endometrial cancer. Advanced cases, especially patients with uterine papillary serous or clear cell histologies may present with abdominal pain and bloating or other symptoms of metastatic disease. Other presenting symptoms may include purulent genital discharge, pain, weight loss, and a change in bladder or bowel habits. Fortunately, most cases of endometrial cancer are diagnosed prior to this clinical presentation because of the recognition of postmenopausal (PMP) bleeding as a possible early symptom of cancer. About 5% of women may be asymptomatic and diagnosed after workup of abnormal Papanicolaou test results.

Uterine sarcomas can present in a similar fashion to endometrial carcinomas. Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) may present in women early in the sixth decade of life with irregular menses or PMP bleeding. Other symptoms include pain, pelvic pressure, and a rapidly enlarging pelvic mass. Unfortunately, the diagnosis is rarely made prior to definitive surgery. Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) usually presents with PMP bleeding, pelvic pain, and an enlarging mass. Like mixed müllerian tumors (MMT), ESS typically presents in the seventh decade of life. Irregular and PMP bleeding are the most common symptoms of MMT also. Weight loss, anorexia, and change in bowel or bladder habits are signs of advanced disease in all cases of uterine cancer.

Indications

The mainstay of primary treatment in endometrial cancer and uterine sarcomas is surgery. Radiation has an important role in adjuvant treatment of endometrial cancers and sarcomas. Chemotherapy plays a role in adjuvant therapy for high-grade uterine sarcomas, in addition to recurrent or metastatic endometrial cancer. Hormonal therapy also has a role in adjuvant therapy in receptor-positive endometrial cancers. Details regarding all of these therapies are discussed later in this article.

Most endometrial cancers are diagnosed as stage I tumors. In fact, most endometrial cancer can be cured with surgery alone, and relatively few patients need adjuvant radiotherapy. In the past, surgery and radiation therapy were both used as primary therapy. Now, survival rates with surgery are known to be 15-20% better than with primary radiation therapy. Thus, primary radiation therapy is reserved only for patients who are poor surgical candidates or for those with unresectable disease.

Like endometrial cancer, primary surgical therapy is the first step in treatment of uterine sarcomas. In fact, these tumors are often found at the time of surgery for benign indications such as uterine leiomyomata and dysfunctional uterine bleeding, or they are found postoperatively. Approximately 1 of every 2000 women older than 40 years who are undergoing a hysterectomy for uterine leiomyomata have leiomyosarcoma (LMS) on final pathologic diagnosis.

Relevant Anatomy

See Multimedia section for relevant surgical anatomy.

Contraindications

In the rare cases of clinical stage I, grade 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma in young women who have not completed childbearing, an attempt can be made to preserve fertility with medical management after careful counseling regarding the potential risks. Full evaluation is needed to rule out higher stage or grade disease. Pelvic ultrasonography, a pelvic MRI, or both is necessary to assess approximate depth of invasion and to rule out adnexal pathology. A hysteroscopy D&C is also necessary to thoroughly sample the endometrial cavity and rule out large volume or higher-grade disease. Prospective and retrospective series report initial response rates of 50-75%, but many will recur. One study reports 25% have achieved pregnancies after conservative management. Recommendation is for definitive total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), and possible staging with disease persistence, recurrence, or at completion ofchildbearing.

Some have suggested ovarian preservation after hysterectomy in young women wishing to preserve hormonal function and future childbearing through egg retrieval. This should be cautioned against due to risk of adnexal metastases or synchronous tumors, which occur in up to 25% of young women.

Women with significant comorbidities who are not surgical candidates and have clinical stage I endometrial cancer can be managed by primary radiation. Although the survival rate with primary radiation alone is 15-20% less than with surgery, the morbidity and mortality from surgical therapy in some patients may outweigh the benefits gained in terms of survival and recurrence. Many of these women will die due to other comorbid conditions.

Treatment Medical Therapy

The treatment of endometrial cancer needs to be individualized depending on patient factors and disease stage. Although surgical therapy and surgicopathologic staging is the mainstay of therapy for most endometrial cancers and uterine sarcomas, nonsurgical therapies, such as radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy, play a role in the treatment of uterine cancers. However, most of these therapies are used as adjuvant/adjunctive therapy or in the treatment of recurrences or metastatic disease.

Of these therapies, only radiotherapy has any place in primary therapy for early endometrial cancer and uterine sarcomas. Primary radiotherapy (total dose to tumor of up to 80 Gy) is the treatment of choice for those patients who are poor surgical candidates. Although the survival rate with primary radiation alone is 15-20% less than with surgery, the morbidity and mortality from surgical therapy in some patients may outweigh the benefits gained in terms of survival and recurrence.

The other instance in which primary radiation is recommended is with stage III disease based on vaginal and/or parametrial extension, where complete resection of the tumor with primary surgery is unlikely. Even in this case, adjuvant hysterectomy and adnexectomy are performed 6 weeks after radiation is completed, when feasible. Treatment of clinical stage IV disease is individualized based on the disease sites. In addition to surgical therapy to control bleeding, radiation therapy is usually administered for symptomatic bone and CNS metastases, as well as for local tumor control if the tumor extends to the bladder or rectum. Primary hormone therapy and chemotherapy may be indicated with distant disease. Primary radiation for uterine sarcomas is usually limited to those patients who are medically inoperable.

Surgical Therapy

For most patients, the recommended primary treatment is surgical excision and staging. Surgical staging involves abdominal exploration, obtaining pelvic washings, total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, biopsy of any suspicious lesions, and pelvic +/- para-aortic lymphadenectomy. If papillary serous or clear cell carcinoma is present, omental biopsy is also required for full staging. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and AJCC stage classifications are based on surgical-pathological findings.

Clinically early stages

Many gynecologic oncologists use the grade and intraoperative frozen analysis of the uterine specimen to determine the extent of lymph node staging performed. Some oncologists treat patients with well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinomas of the endometrium without adverse risk factors (eg, no deep myometrial invasion and tumor size < 2 cm) by simple total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO). However, many will perform a full bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy for every endometrial cancer patient. The rationale for this more aggressive approach is frozen analysis of the grade and depth of endometrial cancer is notoriously unreliable, with upgrading from grade 1 or less in 61% and upstaging in 28% of specimens on final pathology.A complete lymph node dissection would prevent the need to return to the operating room (OR) for lymph node staging or use of unnecessary radiation therapy.

One recent study found that almost 20% of patients with grade 1 disease who underwent routine staging, avoided whole-pelvic radiation based on pathologic findings. Also, a small percentage of patients with grade 1 disease required whole-pelvic radiation that they would not have received based on uterine and adnexal pathology. In addition, controversy exists as to whether lymph node sampling is adequate or if more extensive full lymphadenectomy might offer a survival advantage.

Laparoscopic or robot-assisted staging is becoming increasingly common. Laparoscopy offers less intraoperative blood loss, less complications, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery with comparable lymph node yield. Significantly longer operative times were reported. Comparable disease-free and over-all survival is seen thus far.Concerns have been raised regarding seeding of laparoscopic port sites, tubal spillage of tumor, or vaginal cuff metastases due to uterine manipulation. No data are available to support an increase in these complications, but care should be used to decrease possible seeding by decreasing uterine manipulation, fulguration of tubes upon entry, and removal of large lymph nodes and specimens using endo-pouches.

Morbidity with extended staging when performed by surgeons trained in these techniques is not dramatically increased. Most gynecologic oncologists suggest performing at least limited staging for all patients with endometrial cancer because a significant upgrade or deeper microscopic myoinvasion (15% in some series) may be missed on frozen section and gross examination. However, some patients, specifically elderly patients or those with significant comorbidities, are better served by extrafascial hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy alone, followed by radiation as indicated by histologic factors, even in light of adverse risk factors. Vaginal hysterectomy may be used in the morbidly obese or medically infirm patient who may tolerate the vaginal approach better than the abdominal or laparoscopic approach. Recent studies demonstrate similar survival rates for clinical stage I disease.

In cases of gross cervical involvement, the traditional procedure is a Wertheim radical hysterectomy with BPPLND followed by postoperative radiation (vaginal brachytherapy or whole-pelvic radiotherapy based on pathologic results). TAH/BSO and BPPLND followed by whole-pelvic postoperative radiation based on pathologic results have been suggested to be adequate for clinical stage II disease.

Advanced stages

The significance and management of positive cytology in the absence of other peritoneal or retroperitoneal disease is controversial. Some evidence suggests the endometrial cancer cell in the washings without other high-risk factors, such as high grade, or other extra-uterine disease may not lead to worse outcome and may not need aggressive intervention. This may be caused by uterine manipulation or tubal spillage after hysteroscopy. Others found it to be an independent predictor of worse survival, similar to those patients with positive adnexal or serosal disease.

If bulky disease is found at laparotomy, optimal cytoreduction is recommended to improve patient outcome All patients with advanced stages III and IV disease should be offered adjuvant treatment after surgery. The role of surgery in stage IVB disease may involve tumor reduction or palliative chemotherapy or radiation. Tumor reductive surgery is typically followed with adjuvant/adjunctive chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and/or radiation therapy.

Surgery with staging is also the primary treatment of choice for uterine sarcomas. Patients with leiomyosarcoma (LMS), mixed müllerian tumors (MMT), or high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HGESS) benefit from total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy through a vertical midline incision, with pelvic washings, omental biopsy, and selective pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Lymphadenectomy for low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LGESS) is of limited value because the incidence of lymph node metastases is low. The difficulty with LMS and LGESS is that the diagnosis is usually made intraoperatively or postoperatively. HGESS and MMT are typically diagnosed preoperatively. Subsequently, surgical therapy for patients with LMS and LGESS is often incomplete unless surgeons comfortable with extensive staging are available. The management dilemma is dealt with in the postoperative period.

Preoperative Details

After diagnosis of endometrial cancer or uterine sarcoma is made, preoperative workup should include complete blood cell count, electrolytes, CA-125 (if indicated by atypical presentation or histology), chest radiographs, and any of the above-noted tests, as indicated. Also, the patient should be in compliance with routine health maintenance screening (ie, mammography, Papanicolaou test, sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy as indicated by the patient’s age or symptoms).

If the patient has specific symptoms such as neurologic abnormalities, bone pain, or respiratory symptoms, a directed metastatic workup should be performed preoperatively (eg, head CT scan/MRI, bone scan). Other tests that are occasionally used are CT, MRI, PET/CT, proctosigmoidoscopy, and cystoscopy. These studies are more important in the patient who is medically inoperable. Nonsurgical treatment can then be individualized for these patients. An early referral to a gynecologic oncologist should be made for complete preoperative workup and discussion of extensive staging and cytoreductive surgery or nonsurgical management options.