Pharyngeal Cancer

Treatment and Diagnosis:

If you have symptoms of cancer of the larynx, the doctor may do some or all of the following exams:

- Physical exam. The doctor will feel your neck and check your thyroid, larynx, and lymph nodes for abnormal lumps or swelling. To see your throat, the doctor may press down on your tongue.

- Indirect laryngoscopy. The doctor looks down your throat using a small, long-handled mirror to check for abnormal areas and to see if your vocal cords move as they should. This test does not hurt. The doctor may spray a local anesthesia in your throat to keep you from gagging. This exam is done in the doctor's office.

- Direct laryngoscopy. The doctor inserts a thin, lighted tube called a laryngoscope through your nose or mouth. As the tube goes down your throat, the doctor can look at areas that cannot be seen with a mirror. A local anesthetic eases discomfort and prevents gagging. You may also receive a mild sedative to help you relax. Sometimes the doctor uses general anesthesia to put a person to sleep. This exam may be done in a doctor's office, an outpatient clinic, or a hospital.

- CT scan. An x-ray machine linked to a computer takes a series of detailed pictures of the neck area. You may receive an injection of a special dye so your larynx shows up clearly in the pictures. From the CT scan, the doctor may see tumors in your larynx or elsewhere in your neck.

- Biopsy. If an exam shows an abnormal area, the doctor may remove a small sample of tissue. Removing tissue to look for cancer cells is called a biopsy. For a biopsy, you receive local or general anesthesia, and the doctor removes tissue samples through a laryngoscope. A pathologist then looks at the tissue under a microscope to check for cancer cells. A biopsy is the only sure way to know if a tumor is cancerous.

If you need a biopsy, you may want to ask the doctor the following questions:

- What kind of biopsy will I have? Why?

- How long will it take? Will I be awake? Will it hurt?

- How soon will I know the results?

- Are there any risks? What are the chances of infection or bleeding after the biopsy?

- If I do have cancer, who will talk with me about treatment? When?

Staging

To plan the best treatment, your doctor needs to know the stage, or extent, of your disease. Staging is a careful attempt to learn whether the cancer has spread and, if so, to what parts of the body. The doctor may use x-rays, CT scans, or magnetic resonance imaging to find out whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes, other areas in your neck, or distant sites

Treatment

People with cancer of the larynx often want to take an active part in making decisions about their medical care. It is natural to want to learn all you can about your disease and treatment choices. However, shock and stress after a diagnosis of cancer can make it hard to remember what you want to ask the doctor. Here are some ideas that might help:

- Make a list of questions.

- Take notes at the appointment.

- Ask the doctor if you may use a tape recorder during the appointment.

- Ask a family member or friend to come to the appointment with you.

Your doctor may refer you to a specialist who treats cancer of the larynx, such as a surgeon, otolaryngologist (an ear, nose, and throat doctor), radiation oncologist, or medical oncologist. You can also ask your doctor for a referral. Treatment usually begins within a few weeks of the diagnosis. Usually, there is time to talk to your doctor about treatment choices, get a second opinion, and learn more about the disease before making a treatment decision

Getting a Second Opinion

Before starting treatment, you might want a second opinion about your diagnosis and treatment plan. Some insurance companies require a second opinion; others may cover a second opinion if you or your doctor requests it. There are a number of ways to find a doctor for a second opinion:

- Your doctor may refer you or you may ask for a referral to one or more specialists. At cancer centers, several specialists often work together as a team. The team may include a surgeon, radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, speech pathologist, and nutritionist. At some cancer centers, you may be able to see them all on the same day.

- A local medical society, a nearby hospital, or a medical school can often provide the names of specialists in your area

Preparing for Treatment

The doctor can describe your treatment choices and the results you can expect for each treatment option. You will want to consider how treatment may change the way you look, breathe, and talk. You and your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your needs and personal values.

The choice of treatment depends on a number of factors, including your general health, where in the larynx the cancer began, the size of the tumor, and whether the cancer has spread.

If you smoke, a good way to prepare for treatment is to stop smoking. Studies show that treatment is more likely to be successful for people who don’t smoke.

You may want to talk with the doctor about taking part in a clinical trial, a research study of new treatment methods. Clinical trials are an important option. Patients who join trials have the first chance to benefit from new treatments that have shown promise in earlier research.

These are questions you may want to ask your doctor before treatment begins:

- Where is my cancer and has it spread?

- What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Why?

- What are the benefits of each treatment?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment?

- How will I look after treatment?

- How will I speak after treatment? Will I need to work with a speech therapist?

- Will I have problems eating?

- Will I need to change my daily activities?

- When can I return to work?

- What is the treatment likely to cost? Is this treatment covered by my insurance plan?

- Would a clinical trial (research study) be right for me? Can you help me find one?

- How often will I need checkups?

You do not need to ask all your questions or understand all the answers at once. You will have many chances to ask the doctor and the rest of the health care team to explain things that are not clear and to ask for more information

Methods of Treatment

Cancer of the larynx may be treated with radiation therapy, surgery, or chemotherapy. Some patients have a combination of therapies.

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses high-energy x-rays to kill cancer cells. The rays are aimed at the tumor and the tissue around it. Radiation therapy is local therapy. It affects cells only in the treated area. Treatments are usually given 5 days a week for 5 to 8 weeks.

Laryngeal cancer may be treated with radiation therapy alone or in combination with surgery or chemotherapy:

- Radiation therapy alone: Radiation therapy is used alone for small tumors or for patients who cannot have surgery.

- Radiation therapy combined with surgery: Radiation therapy may be used to shrink a large tumor before surgery or to destroy cancer cells that may remain in the area after surgery. If a tumor grows back after surgery, it is often treated with radiation.

- Radiation therapy combined with chemotherapy: Radiation therapy may be used before, during, or after chemotherapy.

After radiation therapy, some people need feeding tubes placed into the abdomen. The feeding tube is usually temporary.

These are questions you may want to ask your doctor before having radiation therapy:

- Why do I need this treatment?

- What are the risks and side effects of this treatment?

- Are there any long-term effects?

- Should I see my dentist before I start treatment?

- When will the treatments begin? When will they end?

- How will I feel during therapy?

- What can I do to take care of myself during therapy?

- Can I continue my normal activities?

- How will my neck look afterward?

- What is the chance that the tumor will come back?

- How often will I need checkups?

Surgery is an operation in which a doctor removes the cancer using a scalpel or laser while the patient is asleep. When patients need surgery, the type of operation depends mainly on the size and exact location of the tumor.

There are several types of laryngectomy (surgery to remove part or all of the larynx):

- Total laryngectomy: The surgeon removes the entire larynx.

- Partial laryngectomy (hemilaryngectomy): The surgeon removes part of the larynx.

- Supraglottic laryngectomy: The surgeon takes out the supraglottis, the top part of the larynx.

- Cordectomy: The surgeon removes one or both vocal cords.

Sometimes the surgeon also removes the lymph nodes in the neck. This is called lymph node dissection. The surgeon also may remove the thyroid.

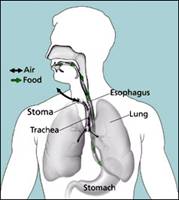

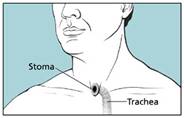

During surgery for cancer of the larynx, the surgeon may need to make a stoma. (This surgery is called a tracheostomy.) The stoma is a new airway through an opening in the front of the neck. Air enters and leaves the windpipe (trachea) and lungs through this opening. A tracheostomy tube, also called a trach (“trake”) tube, keeps the new airway open. For many patients, the stoma is temporary. It is needed only until the patient recovers from surgery.

After surgery, some people may need a temporary feeding tube.

Here are some questions to ask the doctor before having surgery:

- How will I feel after the operation?

- Will I need a tracheostomy?

- Will I need to learn how to take care of myself or my incision when I get home?

- Where will the scars be? What will they look like?

- Will surgery affect my ability to speak? If so, who will teach me how to speak in a new way?

- When can I get back to my normal activities?

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. Your doctor may suggest one drug or a combination of drugs. The drugs for cancer of the larynx are usually given by injection into the bloodstream. The drugs enter the bloodstream and travel throughout the body.

Chemotherapy is used to treat laryngeal cancer in several ways:

- Before surgery or radiation therapy: In some cases, drugs are given to try to shrink a large tumor before surgery or radiation therapy.

- After surgery or radiation therapy: Chemotherapy may be used after surgery or radiation therapy to kill any cancer cells that may be left. It also may be used for cancers that have spread.

- Instead of surgery: Chemotherapy may be used with radiation therapy instead of surgery. The larynx is not removed and the voice is spared.

Chemotherapy may be given in an outpatient part of the hospital, at the doctor’s office, or at home. Rarely, a hospital stay may be needed.

These are questions you may want to ask your doctor before having chemotherapy:

- Why do I need this treatment?

- What will it do?

- Will I have side effects? What can I do about them?

- How long will I be on this treatment?

- How often will I need checkups?

Side Effects of Cancer Treatment

Cancer treatments are very powerful. Treatments that remove or destroy cancer cells are likely to damage healthy cells, too. That's why treatments often cause side effects. This section describes some of the side effects of each kind of treatment.

Side effects may not be the same for each person, and they may even change from one treatment session to the next. Before treatment starts, your health care team will explain possible side effects and how they can be managed. It may help to know that although some side effects may not go away completely, most of them become less troubling.

It may also help to talk with other patients. A social worker, nurse, or other member of the medical team can set up a visit with someone who has had the same treatment

Radiation Therapy

People treated with radiation therapy may have some or all of these side effects:

- Dry mouth. Drinking lots of fluids can help. Some patients find artificial saliva helpful. It comes in a spray or squeeze bottle.

- Sore throat or mouth. Your health care provider may suggest special rinses to numb your throat and mouth and help relieve the soreness.

- Delayed healing after dental care. Many doctors recommend having a dental exam and any needed dental work before radiation therapy.

- Tooth decay. Good mouth care can help keep your teeth and gums healthy and can help you feel better. If it's hard to floss or brush your teeth in the usual way, you can try using gauze, a soft toothbrush, or a toothbrush that has a spongy tip instead of bristles. A mouthwash made with diluted peroxide, salt water, baking soda, or a combination can keep your mouth fresh and help protect your teeth from decay. It may also be helpful to use fluoride toothpaste or rinse.

- Changes in sense of taste and smell. During radiation therapy, food may taste or smell different.

- Fatigue. During radiation therapy, you may become very tired, especially in the later weeks of treatment. Resting is important, but doctors usually advise their patients to stay as active as they can.

- Changes in voice quality. Your voice may be weak at the end of the day. It may also be affected by changes in the weather. Voice changes and the feeling of a lump in your throat may come from swelling in the larynx caused by the radiation. The doctor may suggest medicine to reduce this swelling.

- Skin changes in treated area. The skin in the treated area may become red or dry. Good skin care is important at this time. Try to expose this area to the air but protect it from the sun. Avoid wearing clothes that rub, and do not shave the treated area. You should not put anything on your skin before radiation treatments. Also, you should never use lotion or cream without your doctor's advice

Surgery

People who have surgery may have any of these side effects:

- Pain. You may be uncomfortable for the first few days after surgery. However, medicine can usually control the pain. You should feel free to discuss pain relief with the doctor or nurse.

- Low energy. It is common to feel tired or weak after surgery. The length of time it takes to recover from an operation is different for each patient.

- Swelling in the throat. For a few days after surgery, you won’t be able to eat, drink, or swallow. At first, you will receive fluid through an intravenous (IV) tube placed into your arm. Within a day or two, you will get fluids and nutrition through a feeding tube (put in place during surgery) that goes through your nose and throat into your stomach. When the swelling goes away and the area begins to heal, the feeding tube will be removed. Swallowing may be difficult at first, and you may need the help of a nurse or speech pathologist. Soon you will be eating your regular diet.

If you need a feeding tube for longer than one week, you may get a tube that goes directly into the abdomen. Most patients slowly return to eating solid foods by mouth, but for a very few patients, the feeding tube may be permanent.

- Increased mucus production. After the operation, the lungs and windpipe produce a lot of mucus, also called sputum. To remove it, the nurse applies gentle suction by placing a small plastic tube in the stoma. You will learn to cough and suction mucus through the stoma without the nurse's help.

- Numbness, stiffness, or weakness. After a laryngectomy, parts of the neck and throat may be numb because nerves have been cut. Also, the shoulder, neck, and arm may be weak and stiff. You may need physical therapy to improve your strength and flexibility after surgery.

- Changes in physical appearance. Your neck will be somewhat smaller, and it will have scars. Some patients find it helpful to wear clothing that covers the neck area.

- Tracheostomy. Patients who have surgery will have a stoma. With most supraglottic and partial laryngectomies, the stoma is temporary. After a short recovery period, the tube can be removed, and the stoma closes up. You should then be able to breathe and talk in the usual way. In some people, however, the voice may be hoarse or weak.

After a total laryngectomy, the stoma is permanent. If you have a total laryngectomy, you will need to learn to speak in a new way.

Chemotherapy

The side effects of chemotherapy depend mainly on the specific drugs and the dose. In general, anticancer drugs affect cells that divide rapidly:

- Blood cells: These cells fight infection, help your blood to clot, and carry oxygen to all parts of your body. If your blood cells are affected, you are more likely to get infections, may bruise or bleed easily, and may feel very weak and tired.

- Cells in hair roots: Chemotherapy can lead to hair loss, but hair will grow back. However, the new hair may be different in color and texture.

- Cells that line the digestive tract: Chemotherapy can cause poor appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or mouth and lip sores. Many of these side effects can be controlled with new or improved drugs